BBC Culture

Including the time a US president expressed sexual desire for an entire nation.

The greatest mistranslations ever

After an unfortunate Google Translate update last year, BBC Culture looked back on history’s biggest language mistakes – including one that raised tensions in the Cold War.

BBC.COM|由 FIONA MACDONALD 上傳

http://www.bbc.com/culture/story/20150202-the-greatest-mistranslations-ever

Google Translate’s latest update – turning the app into a real-time interpreter – has been heralded as bringing us closer to ‘a world where language is no longer a barrier’. Despite glitches, it offers a glimpse of a future in which there are no linguistic misunderstandings – especially ones that change the course of history. BBC Culture looks back at the greatest mistranslations of the past, with a 19th-Century astronomer finding signs of intelligent life on Mars and a US president expressing sexual desire for an entire nation.

Life on Mars

When Italian astronomer Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli began mapping Mars in 1877, he inadvertently sparked an entire science-fiction oeuvre. The director of Milan’s Brera Observatory dubbed dark and light areas on the planet’s surface ‘seas’ and ‘continents’ – labelling what he thought were channels with the Italian word ‘canali’. Unfortunately, his peers translated that as ‘canals’, launching a theory that they had been created by intelligent lifeforms on Mars.

Convinced that the canals were real, US astronomer Percival Lowell mapped hundreds of them between 1894 and 1895. Over the following two decades he published three books on Mars with illustrations showing what he thought were artificial structures built to carry water by a brilliant race of engineers. One writer influenced by Lowell’s theories published his own book about intelligent Martians. In The War of the Worlds, which first appeared in serialised form in 1897, H G Wells described an invasion of Earth by deadly Martians and spawned a sci-fi subgenre. A Princess of Mars, a novel by Edgar Rice Burroughs published in 1911, also features a dying Martian civilisation, using Schiaparelli’s names for features on the planet.

While the water-carrying artificial trenches were a product of language and a feverish imagination, astronomers now agree that there aren’t any channels on the surface of Mars. According to Nasa, “The network of crisscrossing lines covering the surface of Mars was only a product of the human tendency to see patterns, even when patterns do not exist. When looking at a faint group of dark smudges, the eye tends to connect them with straight lines.”

Pole position

Jimmy Carter knew how to get an audience to pay attention. In a speech given during the US President’s 1977 visit to Poland, he appeared to express sexual desire for the then-Communist country. Or that’s what his interpreter said, anyway. It turned out Carter had said he wanted to learn about the Polish people’s ‘desires for the future’.

Earning a place in history, his interpreter also turned “I left the United States this morning” into “I left the United States, never to return”; according to Time magazine, even the innocent statement that Carter was happy to be in Poland became the claim that “he was happy to grasp at Poland's private parts”.

Unsurprisingly, the President used a different interpreter when he gave a toast at a state banquet later in the same trip – but his woes didn’t end there. After delivering his first line, Carter paused, to be met with silence. After another line, he was again followed by silence. The new interpreter, who couldn’t understand the President’s English, had decided his best policy was to keep quiet. By the time Carter’s trip ended, he had become the punchline for many a Polish joke.

Keep digging

Google Translate might not have been able to prevent one error that turned down the temperature by several degrees during the Cold War. In 1956, Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev was interpreted as saying “We will bury you” to Western ambassadors at a reception at the Polish embassy in Moscow. The phrase was plastered across magazine covers and newspaper headlines, further cooling relations between the Soviet Union and the West.

Yet when set in context, Khruschev’s words were closer to meaning “Whether you like it or not, history is on our side. We will dig you in”. He was stating that Communism would outlast capitalism, which would destroy itself from within, referring to a passage in Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto that argued “What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers.” While not the most calming phrase he could have uttered, it was not the sabre-rattling threat that inflamed anti-Communists and raised the spectre of a nuclear attack in the minds of Americans.

Khruschev himself clarified his statement – although not for several years. “I once said ‘We will bury you’, and I got into trouble with it,” he said during a 1963 speech in Yugoslavia. “Of course we will not bury you with a shovel. Your own working class will bury you.”

Diplomatic immunity

Mistranslations during negotiations have often proven contentious. Confusion over the French word ‘demander’, meaning ‘to ask’, inflamed talks between Paris and Washington in 1830. After a secretary translated a message sent to the White House that began “le gouvernement français demande” as “the French government demands”, the US President took issue with what he perceived as a set of demands. Once the error was corrected, negotiations continued.

Some authorities have been accused of exploiting differences in language for their own ends. The Treaty of Waitangi, a written agreement between the British Crown and the Māori people in New Zealand, was signed by 500 tribal chiefs in 1840. Yet conflicting emphases in the English and Māori versions have led to disputes, with a poster claiming ‘The Treaty is a fraud’ featuring in the Māori protest movement.

Taking the long view

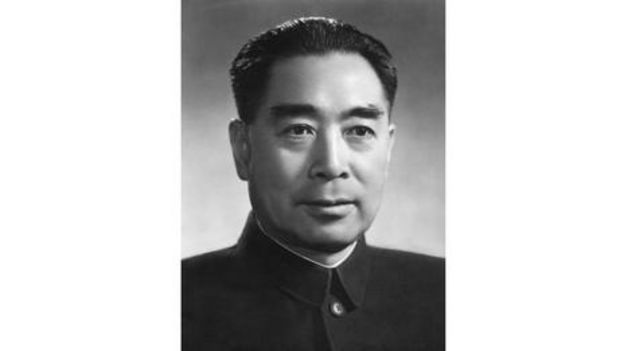

More of a misunderstanding than a mistranslation, one often-repeated phrase might have been reinforced by racial stereotypes. During Richard Nixon’s visit to China in 1972, Chinese premier Zhou Enlai famously said it was ‘too early to tell’ when evaluating the effects of the French Revolution. He was praised for his sage words, seen as reflecting Chinese philosophy; yet he was actually referring to the May 1968 events in France.

According to retired US diplomat Charles W Freeman Jr – Nixon’s interpreter during the historic trip – the misconstrued comment was “one of those convenient misunderstandings that never gets corrected.” Freeman said: “I cannot explain the confusion about Zhou’s comment except in terms of the extent to which it conveniently bolstered a stereotype (as usual with all stereotypes, partly perceptive) about Chinese statesmen as far-sighted individuals who think in longer terms than their Western counterparts.

“It was what people wanted to hear and believe, so it took hold.”

在谷歌翻譯出現之前的史上重大翻譯失誤

- 2015年 6月 25日

谷歌翻譯升級——谷歌翻譯變身實時翻譯,這一直被認為是一個創舉,它拉近了我們彼此的距離,讓「語言不再成為我們溝通的阻礙」。儘管會出現各種失誤,但谷歌翻譯的確呈現給世人一個不再有語言誤解的未來,特別是那些曾改變歷史進程的失誤。BBC Culture 將回顧歷史上一些重大翻譯失誤,其中就包括 19 世紀某位天文學家發現火星上的智慧生命跡象以及美國總統表達自己對某個國家的生理慾望。

火星上的生命

1877 年,意大利天文學家夏帕雷利(Giovanni Virginio Schiaparelli)著手繪製火星地圖,他的不經意之舉竟然激發了一部科幻作品的誕生。這位意大利米蘭布雷拉天文台(Brera Observatory)負責人將火星表面錯落分佈的黑暗區域和光亮區域稱為『海洋』和『陸地』——並在他認為的溝渠處用意大利語『canali』加以標注。不幸的是,他的同事將「canali」(溝渠)翻譯為「canals」(運河),由此提出一個理論,認為火星上的某種智慧生命修建了這些運河。

由於深信這些運河真的存在,美國天文學家帕西瓦爾·羅威爾(Percival Lowell)在 1894-1895 年間繪製了成百上千張火星運河地圖。隨後的二十多年裏,他出版了三部火星專著,書中插圖描繪了他想像中的火星人造運河,他認為這些運河都出自才華橫溢的火星工程師之手。受羅威爾理論的啟發,一位作家也還出版了關於火星智慧生命的著作。

1897 年,《世界大戰》(The War of the Worlds)首次以連載形式出版,作者威爾斯(H G Wells)在其中描述了死到臨頭的火星人對地球的一次入侵,他的著作也開創了科幻小說的一個新門類。埃德加·賴斯·巴勒斯(Edgar Rice Burroughs)於 1911 出版了小說 《火星公主》(A Princess of Mars),它也描寫了一個即將滅亡的火星文明,其中以斯基亞帕雷利(Schiaparelli)作為火星人的名字。

實際上,人造運河只是語言誤譯與狂熱想像的產物,天文學家現在認為,火星表面並無任何溝渠存在。根據美國航空航天局(NASA)的說法,「火星表面交錯分佈的網狀線條僅僅是人們觀察時產生的錯覺,事實上並不存在。」在觀察一組模糊的黑點時,人的眼睛往往會將其誤認為直線。

波蘭的定位

吉米·卡特(Jimmy Carter)深知怎樣才能吸引聽眾的注意力。在 1977 年對波蘭的訪問中,美國總統卡特對當時還是社會主義國家的波蘭表達了自己的生理慾望。或者說,無論如何,他的譯員就是這樣翻譯的。 實際上,卡特的原話是,他想了解波蘭人「對未來的期盼」。

更有甚者,卡特講話中的「我今天早上離開美國」被翻譯成「我離開了美國,永遠都回不去了」,他的譯員因此名垂青史。據《時代》雜誌報道,即使卡特最無辜的表白「很高興來到波蘭」,也被翻譯成「他很高興抓住波蘭的私處」。

鑒於此,在此行隨後的國宴上致辭時,卡特更換口譯也就不足為奇,但美國總統的悲劇卻並未終結。致辭中,卡特說完第一句,為翻譯停頓了一下,但後者毫無反應。卡特又說了一句,翻譯仍舊不出聲。顯然,新任翻譯聽不懂美國總統的英語,只好沉默是金了。訪問結束之時,卡特已經成為許多波蘭人的笑柄。

不停地挖掘

即使谷歌翻譯,可能也無法避免一個令冷戰時期東西方關係雪上加霜的失誤。1956 年,在莫斯科波蘭大使館舉辦的西方使節招待會上,前蘇聯領導人赫魯曉夫的一句講話被翻譯成「我們將埋葬你們」。這句話被搬上雜誌封面和報紙頭條,讓前蘇聯與西方的關係進一步降溫。

實際上,赫魯曉夫這句話在上下文中的意思更接近於「不管你們喜歡與否,歷史都站在我們這一邊,我們將埋葬你們。」他要表達的是,共產主義的生命將比資本主義更為長久,而資本主義將從內部自己毀滅,其借用了卡爾·馬克思《共產黨宣言》中的論述:「因此,最重要的是,資產階級將成為自己的掘墓人。」雖然這不是他所能說出的最為冷靜的話,但他也不是要借此炫耀武力、威脅反共人士、激活美國人心中的核攻擊幽靈。

赫魯曉夫後來對自己講話做出澄清,但這已是數年之後了。1963 年,在南斯拉夫的一次講話中,他表示,「我曾說過『我們將埋葬你們』,因為這句話,我惹上了麻煩,我們當然不會用鐵鍬埋葬你們,你們的工人階級就會埋葬你們。」

外交豁免權

談判中的翻譯失誤往往導致爭議。法語詞「demander」的意思是「請求」,1830 年,因為對它的理解不清,導致巴黎和華盛頓之間會談的白熱化。「le gouvernement français demande(法國政府請求)」被一名秘書翻譯為「法國政府要求」發回白宮,而美國總統對於他所認為的一系列要求持強烈反對意見。在翻譯失誤被糾正後,會談才得以繼續。

有關當局屢屢因利用字眼差別達成自身目的而遭受指責。懷唐伊條約(The Treaty of Waitangi)是 1840 年英國王室與新西蘭毛利人之間達成的一項書面協議,由 500 位部落首領簽署。但該協議的英文版本和毛利語版本存在衝突重點,由此導致爭議,毛利人在抗議運動中打出「協議是欺詐」的標語。

長遠的眼光

還有一個例子與其說是翻譯失誤,不如說是誤會,在談到種族偏見時,它往往被反覆提及。1972 年理查德·尼克松(Richard Nixon)訪問中國,中國總理周恩來在談到法國大革命的影響時,說過一句著名的話:「言之尚早」。這句富有中國哲理的評論被廣為傳頌,但實際上,他談到的並非法國大革命,而是法國 1968 年的五月風暴。

美國前外交官小查爾斯·W·弗裏曼(Charles W Freeman Jr) 在那次歷史性的訪華之旅中擔任尼克松的翻譯,據他回憶,這句被誤會的評論是「一個方便的誤會,永遠不會得到糾正。」弗裏曼表示:「我無法說明對周恩來評論的困惑,只好借著人們對中國政治家的成見(像所有成見一樣,都有失偏頗),認為他們比西方政治家眼光更為長遠,做出了一個方便的解釋。」

「這也正是人們想要聽到、也願意相信的,自然也就被接受了。」

沒有留言:

張貼留言