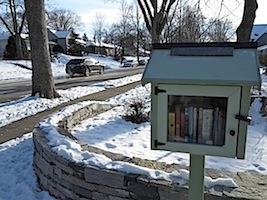

卻找不到

原來是免費的free 請自己取書.....

A Little Free Library in Minneapolis on Dec. 25,

2012. The whimsical little boxes were first started by Todd Bol in

Hudson, Wis., three years ago and have grown into a global phenomenon

since then. (MPR Photo/Hart Van Denburg)

Little Free Library phenomenon started in Hudson, Wis.

December 25, 2012

STEVE KARNOWSKI

Associated Press

HUDSON, Wis. (AP) -- It started as a simple tribute to his mother, a teacher and bibliophile. Todd Bol put up a miniature version of a one-room schoolhouse on a post outside his home in this western Wisconsin city, filled it with books and invited his neighbors to borrow them.

They loved it, and began dropping by so often that his lawn became a gathering spot. Then a friend in Madison put out some similar boxes and got the same reaction. More home-crafted libraries began popping up around Wisconsin's capital.

Three years later, the whimsical boxes are a global sensation. They number in the thousands and have spread to at least 36 countries, in a testimonial to the power of a good idea, the simple allure of a book and the wildfire of the internet.

"It's weird to be an international phenomenon," said Bol, a former international business consultant who finds himself at the head of what has become the Little Free Libraries organization. The book-sharing boxes are being adopted by a growing number of groups as a way of promoting literacy in inner cities and underdeveloped countries.

Bol, his Madison friend Rick Brooks, and helpers run the project from a funky workshop with a weathered wood facade in an otherwise nondescript concrete industrial building outside Hudson, a riverside community of 12,000 about 20 miles east of downtown St. Paul, Minn. They build wooden book boxes in a variety of styles, ranging from basic to a miniature British-style phone booth, and offer them for sale on the group's website, which also offers plans for building your own. Sizes vary. The essential traits are that they are eye-catching and protect the books from the weather.

Each little library invites passersby to "take a book, return a book."

Educators in particular have seized on the potential of something so simple and self-sustaining.

In Minneapolis, school officials are aiming to put up about 100 in neighborhoods where many kids don't have books at home. A box at district headquarters goes through 40 books a day, serving children whose parents come to register them and adults who come to prepare for high school equivalency tests.

"I absolutely love them," said Melanie Sanco, the district's point person on the effort. "It sparks the imagination. You see them around and you want one. ... They're cute and adorable." Kids who have books stay in school longer, she said.

Bol and Brooks, who runs outreach programs at the University of Wisconsin, see the potential for a lot more growth. At one point, they set a goal of 2,510 boxes -- surpassing the number of public libraries built by philanthropist Andrew Carnegie. They passed that mark this summer.

The Rotary Club plans to use the book boxes in its literacy efforts in the west African nation of Ghana. Books for Africa, a Minnesota-based group that has sent over 27 million books to 48 countries since 1988, recently decided to ship books and little libraries to Ghana, too.

The groups are working with Antoinette Ashong, a pro-literacy activist and headmistress of a girls' school in the capital of Accra. "I want to spread reading in Africa, which is a problem because in Africa it is very, very difficult to get books to read," Ashong said in a Skype interview. She has already put up 45 boxes in poor neighborhoods.

Most of the nonprofit's money comes from sale of pre-built little libraries, which cost from $250 to $600, and a $25 fee to register a library on the organization's web site. The AARP Foundation has also provided a $70,000 grant as part of a new program to provide book boxes for seniors and kids to read to them.

Bol and Brooks recently began drawing paychecks after several years of work as volunteers. Bol, the full-time executive director, said he hopes to earn $60,000 a year eventually, but added, "we're not there yet." The group will remain a nonprofit, Bol said, but they want to develop stable revenue streams and management systems so it can continue to grow.

"We are working very hard to get close to making it financially viable, but it will be a while," Brooks said. "What's encouraging is that every day people call us and they have the most clever, interesting and sometimes moving ideas."

Sage Holben, who put up a Little Free Library in her tough neighborhood near downtown St. Paul, said she thinks it has made a positive difference. Although crime and violence are common on the block, no one has vandalized the box or stolen the books, and she routinely sees kids exploring the contents. She said she asked one 8-year-old neighbor if she really intended to read a romance novel she had taken.

The girl told her no, Holben said, but ran her finger over the words as if following the text.

"I do this and I feel like I'm smart," the girl said.

〔國際新聞中心/美聯社威斯康辛州胡德森市26日電〕原本這是為了向他的母親、一名老師與愛書人致敬而設置,但美國威斯康辛州胡德森市男子博爾在家門外架設的「小小自由圖書館」不只大受鄰里好評,類似設施也在全世界造成轟動。

博爾多年前在家門外的草坪搭建了只有一個房間的圖書室,在裡面擺滿書籍,並邀請鄰居踴躍借閱。這個小圖書室其實只是個小箱子,不過可讓經過的人自由借還書的想法,鄰居們實在愛極了,常常跑來共享書香。

後 來,博爾在威州首府麥迪遜的朋友布魯克斯也在家門口設置類似的圖書箱,同樣獲得廣泛回響。一傳十,十傳百,三年後,這種原本只是異想天開的圖書室,竟然在 全球蔚為風潮,現在已有至少三十六國、共數千個類似圖書箱設置,一些內陸城市以及未開發國家甚至把這種圖書箱作為推廣識字率的方式。

博爾與 布魯克斯在明尼蘇達州的工作室,開始推廣「小小自由圖書館」計畫。他們用木材搭建各式各樣的木箱,有的是基本造型,有的像是縮小版的英國造型電話亭,大小 不同,但外型搶眼,能保護書籍抵禦天氣侵襲是共同特色。接著他們在網路上販售木箱,並提供自行搭建「小小自由圖書館」的建議。

「小小自由圖書館」是非營利組織,經費就來自每個250美元到600美元的木箱販售所得,以及在組織官網登記的費用25美元,全美中老年人協會基金會也提供了7萬美元的補助金。

明尼亞波利斯市的學校當局,計畫在孩童沒有自己讀物的社區設置約100個圖書箱。當地圖書箱計畫負責人說,小孩子非常喜歡這種想法,設置圖書箱的地區,孩子們留在學校的時間都比較長。非洲西部國家迦納則利用這種書箱來提升識字率。

意外成為「小小自由圖書館」組織領袖的博爾說:「圖書箱造成國際轟動實在很奇怪。」他認為此項計畫還很有發展的潛力,有一度他訂定廣設2510個圖書箱的目 標,今年夏天他已在慈善家卡內基的協助下達成,原本只是義務幫忙性質的博爾與布魯克斯最近也開始收到酬勞。博爾說,組織會維持非營利性質,不過他希望有些 營利,才能讓組織持續成長。

博爾多年前在家門外的草坪搭建了只有一個房間的圖書室,在裡面擺滿書籍,並邀請鄰居踴躍借閱。這個小圖書室其實只是個小箱子,不過可讓經過的人自由借還書的想法,鄰居們實在愛極了,常常跑來共享書香。

後 來,博爾在威州首府麥迪遜的朋友布魯克斯也在家門口設置類似的圖書箱,同樣獲得廣泛回響。一傳十,十傳百,三年後,這種原本只是異想天開的圖書室,竟然在 全球蔚為風潮,現在已有至少三十六國、共數千個類似圖書箱設置,一些內陸城市以及未開發國家甚至把這種圖書箱作為推廣識字率的方式。

博爾與 布魯克斯在明尼蘇達州的工作室,開始推廣「小小自由圖書館」計畫。他們用木材搭建各式各樣的木箱,有的是基本造型,有的像是縮小版的英國造型電話亭,大小 不同,但外型搶眼,能保護書籍抵禦天氣侵襲是共同特色。接著他們在網路上販售木箱,並提供自行搭建「小小自由圖書館」的建議。

「小小自由圖書館」是非營利組織,經費就來自每個250美元到600美元的木箱販售所得,以及在組織官網登記的費用25美元,全美中老年人協會基金會也提供了7萬美元的補助金。

明尼亞波利斯市的學校當局,計畫在孩童沒有自己讀物的社區設置約100個圖書箱。當地圖書箱計畫負責人說,小孩子非常喜歡這種想法,設置圖書箱的地區,孩子們留在學校的時間都比較長。非洲西部國家迦納則利用這種書箱來提升識字率。

意外成為「小小自由圖書館」組織領袖的博爾說:「圖書箱造成國際轟動實在很奇怪。」他認為此項計畫還很有發展的潛力,有一度他訂定廣設2510個圖書箱的目 標,今年夏天他已在慈善家卡內基的協助下達成,原本只是義務幫忙性質的博爾與布魯克斯最近也開始收到酬勞。博爾說,組織會維持非營利性質,不過他希望有些 營利,才能讓組織持續成長。

沒有留言:

張貼留言